Embedded diagrams and pandoc

24. Januar 2012 um 13:02 Keine KommentareIf you don’t know John MacFarlane’s Pandoc, the „Swiss army knive of document formats“, you should definitely give it a try! Pandoc’s abstract document model and its serialization in an extended variant of Markdown markup let you focus on the structure and content of a text instead of dealing with formats and user interfaces. In my opinion pandoc is the best tool for document creation invented since (La)TeX (moreover pandoc is a good argument to finally learn programming in Haskell) Images in pandoc markdown documents, however, are only referenced by their file. This requires some preprocessing if you want to create different files for different document formats, especially bitmap images and vector images. So I hacked a little preprocessing script that let’s you embed images in pandoc’s markup language. For instance you write

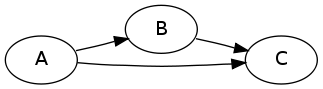

~~~~ {.dot .Grankdir:LR}

digraph {

A -> B -> C;

A -> C;

}

~~~~

and you get

or based on rdfdot you write

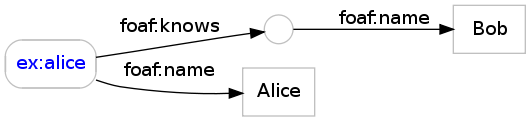

~~~~ {.rdfdot}

@prefix foaf: <http: //xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/> .

@base <http: //example.com/> .

<alice> foaf:name „Alice“ ;

foaf:knows [ foaf:name „Bob“ ] .

~~~~

and you get

A detailed description is included in the manual which has been transformed automatically to HTML and to PDF. Compare both documents to see that HTML includes PNG images and PDF contains vector images!

Feel free to reuse and modify the script, for instance by adding more diagram types! For instance how about ASCII tabs and ABC notation if you write about music?

Linked local library data simplified

10. Januar 2012 um 14:53 1 KommentarA few days ago Lukas Koster wrote an article about local library linked data. He argues that bibliographic data from libraries data as linked data is not „the most interesting type of data that libraries can provide“. Instead „library data that is really unique and interesting is administrative information about holdings and circulation“. So libraries „should focus on holdings and circulation data, and for the rest link to available bibliographic metadata as much as possible.“ I fully agree with this statements but not with the exact method how do accomplish the publication of local library data.

Among other project, Koster points to LibraryCloud to aggregate and deliver library metadata, but it looks like they reinvent yet more wheels in form of their own APIS and formats for search and for bibliographic description. Maybe I am wrong about this project, as they just started to collect holding and circulation data.

At the recent Semantic Web in Bibliotheken conference, Magnus Pfeffer gave a presentation about „Publishing and consuming library loan information as linked open data“ (see slides) and I talked about a Simplified Ontology for Bibliographic Resources (SOBR) which is mainly based on the DAIA data model. We are going to align both data models and I hope that the next libraries will first look at these existing solutions instead of inventing yet another data format or ontology. Koster’s proposal, however, looks like such another solution: he argues that „we need an extra explicit level to link physical Items owned by the library or online subscriptions of the library to the appropriate shared network level“ and suggests to introduce a „holding“ level. So there would be five levels of description:

- Work

- Expression

- Manifestation

- Holding

- Item

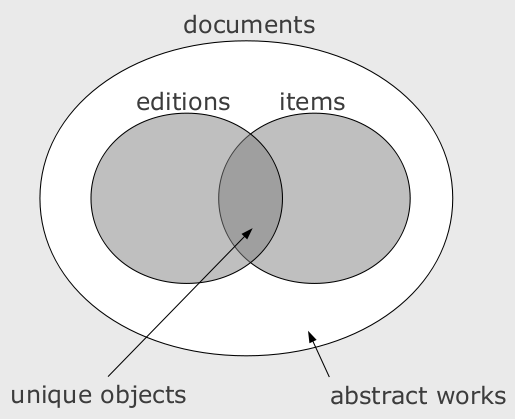

Apart from the fact that at least one of Work, Expression, Manifestation is dispensable, I disagree with a Holding level above the Item. My current model consists of at most three levels of documents:

- document as abstract work (frbr:Work, schema:CreativeWork…)

- bibliographic document (frbr:Manifestation, sobr:Edition…)

- item as concrete single copy (frbr:Item…)

The term „level“ is misleading because these classes are not disjoint. I depicted their relationship in a simple Venn diagram:

For local library data, we are interested in single items, which are copies of general documents or editions. Where do Koster’s „holding“ entities fit into this model? He writes „a specific Holding in this way would indicate that a specific library has one or more copies (Items) of a specific edition of a work (Manifestation), or offers access to an online digital article by way of a subscription.“ The core concepts as I read them are:

- „one or more copies (Items)“ = frbr:Item

- „specific edition of a work (Manifestation)“ = sobr:Edition or frbr:Manifestation

- „has one […] or offer access to“ = ???

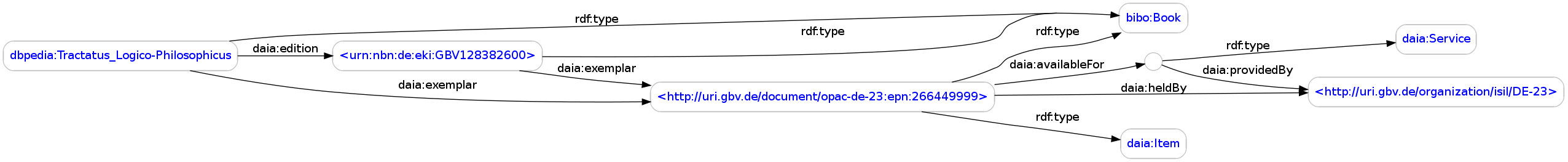

Instead of creating another entity for holdings, you can express the ability „to have one or offer access to“ by DAIA Services. The class daia:Service can be used for an unspecified service and more specific subclasses such as loan, presentation, and openaccess can be used if more is known. Here is a real example with all „levels“:

<http://dbpedia.org/resource/Tractatus_Logico-Philosophicus>

a bibo:Book ;

daia:edition <urn:nbn:de:eki:GBV128382600> ;

daia:exemplar

<http://uri.gbv.de/document/opac-de-23:epn:266449999> .

<urn:nbn:de:eki:GBV128382600> a bibo:Book ;

daia:exemplar

<http://uri.gbv.de/document/opac-de-23:epn:266449999> .

<http://uri.gbv.de/document/opac-de-23:epn:266449999>

a bibo:Book, daia:Item ;

daia:heldBy <http://uri.gbv.de/organization/isil/DE-23> ;

daia:availableFor [

a daia:Service ;

daia:providedBy <http://uri.gbv.de/organization/isil/DE-23>

] .

I have only made up the RDF property daia:edition from the SOBR proposal because FRBR relations are too strict. If you know a better relation to directly relate an abstract work to a concrete edition, please let me know.

image created with rdfdot

Request for comments: final specification of DAIA

6. Januar 2012 um 12:13 4 KommentareWhen I started to create an API for availability lookup of document in libraries in 2008, I was suprised that such a basic service was so poorly defined. The best I could find was the just-published recommendation of the Digital Library Federation (DLF-ILS). Even there availability status was basically a plain text message (section 6.3.1 and appendix 4 and 5). Other parts of the DLF-ILS GetAvailability response were more helpful, so they are all part of the Document Availability Information API (DAIA). Here is a simple mapping from DLF-ILS to DAIA:

- bibliographicIdentifer (string) → document (URI)

- itemIdentifier (string) → item (URI)

- dateAvailable (dateTime) → expected (xs:dateTime or xs:date or „unknown“) or delay (xs:duration or „unknown“)

- location (string) → storage (URI and/or string, plus optional URL)

- call number (string) → label (string)

- holdQueueLength (int) → queue (xs:nonNegativeInteger)

- status (string) and circulating (boolean) → available/unavailable (with service type and additional information)

So you could say that DAIA implements the abstract GetAvailability function from DLF-ILS. I like abstract, language independent specifications, but they must be precise and testable (see Meek’s forgotten paper The seven golden rules for producing language-independent standards). DAIA is more than an implementation: it provides both, an abstract standard and bindings to several data languages (XML, JSON, and RDF). The conceptual DAIA data model defines some basic concepts and relationships (document, items, organisations, locations, services, availabilities, limitations…) independent from whether they are expressed in XML elements, attributes, RDF properties, classes, or any other data structuring method. The only reference to specific formats is the requirement that all unique identifiers must be URIs. Right now there is an XML Schema if you want to express DAIA in XML and an OWL ontology for RDF.

In its fourth year of development (see my previous posts from 2009) DAIA seems to have enough momentum to finally get accepted in practice. We use it in GBV library union (public server at http://daia.gbv.de/), there are independent implementations such as in Doctor-Doc, there is client-support in VuFind and I heard rumors that DAIA capabilities will be build into EBSCO and Summon Discovery Services. Native support in Integrated Library Systems, however, is still lacking – I already have given up hope and prefer a clean DAIA wrapper over a broken DAIA-implementation anyway. If you are interested in creating your own DAIA server/wrapper or client, have a look at my reference implementation DAIA and Plack::App::DAIA at CPAN and Oliver Goldschmidt’s PHP implementation in our common github repository. A conceptual overview as tree (DAIA/JSON, DAIA/XML) and as graph (DAIA/RDF) can be found here.

Still there are some details to be defined and I’d like to solve these issues to come to a version DAIA 1.0. These are

- How to deal with partial publications (you requested an article but only get the full book or you requested a series but only get a single volume).

- How to deal with digital publications (especially its possible service types: is „download“ a service distinct to „loan“ or is „presentation“ similar to online access restricted to the library’s intranet?).

- Final agreement on service types (now there are presentation: item can be used in the institution, loan: item can be used outside of the institution for a limited time, interloan: item can be send to another institution, openaccess: item can be access unrestricted, just get a free copy). Some extensions have been proposed.

- A set of common limitation types (for instance IP-based access restriction, permission-based access etc.).

I’d be happy to get some more feedback on these issues, especially concrete use cases. We are already discussing on the daia-devel mailing list but you can also comment in your own blog, at public-lld, code4lib, ils-di etc.).

P.S: Following an article by Adrian I started to collect open questions and comments as issues at github

Wikipedia ist keine Loseblattsammlung

12. Dezember 2011 um 23:34 1 KommentarSeit mittlerweile sieben Jahren gibt es mit dem Wikipedia-Portal Bibliothek, Information, Dokumentation eine Übersicht der Wikipedia-Artikel aus dem BID-Bereich. Ich gehe davon aus, dass alle Studieren der Bibliotheks- und Informationswissenschaft die dort aufgeführten Wikipedia-Inhalte auch für ihr Studium nutzen.

Wenn ich mir die Artikel anschaue, die Christoph Demmer unermüdlich als neu angelegt im BID-Portal einträgt (vielen Dank!), frage ich mich allerdings manchmal, ob das Projekt nicht gescheitert ist (wieder so eine Idee für einen LIBREAS-Artikel zum Thema Scheitern). Es ist zwar nicht so, dass Wikipedia nicht oder nur passiv verwendet würde. Der Anteil derer, die sich trauen, einen Fehler zu korrigieren oder fehlende Informationen und Zusammenhänge einzutragen, liegt eben nur im einstelligen Prozentbereich. Vereinzelt finden sich sich aber sowohl Studierende als auch Institutionen und ihre Mitarbeiter, die etwas zu Wikipedia beisteuern. Die neuen Artikel sind auch nicht unbedingt schlecht, sie müssen in der Regel nur etwas angepasst werden. Trotzdem bleibt ein wenig Enttäuschung, wenn ich mir Artikel zu Bibliotheken, Bibliothekaren und den Phänomenen mit denen sie sich beschäftigen, in Wikipedia anschauen. Was ist das Problem?

Ich glaube, dass viele Menschen Wikipedia als Loseblattsammlung missverstehen: ab und zu kommen Änderungen und neue Artikel, die Artikel haben einige Links, aber das war es auch schon. Weder dem Austausch zwischen den Wikipedia-Autoren noch dem Hypertext-Charakter der Online-Enzykopädie als Gesamtsystem wird diese Vorstellung gerecht. Dabei finde ich viel wichtiger dass Wikipedia Denkanstöße schafft, Zusammenhänge aufzeigt und einen Überblick bieten kann. Neue Artikel, wie zum Beispiel Elektronische Bibliothek Schweiz oder Primo Central, stehen jedoch eher da wie Inseln im Informationsdschungel, um eine mißglückte Metapher zu bemühen (@LIBREAS habt ihr was zu gescheiterten Metaphern?). Auf den Inseln lässt sich es sich zwar leben, geographische Grundkenntnisse bleiben aber begrenzt.

Ich glaube, dass viele Menschen Wikipedia als Loseblattsammlung missverstehen: ab und zu kommen Änderungen und neue Artikel, die Artikel haben einige Links, aber das war es auch schon. Weder dem Austausch zwischen den Wikipedia-Autoren noch dem Hypertext-Charakter der Online-Enzykopädie als Gesamtsystem wird diese Vorstellung gerecht. Dabei finde ich viel wichtiger dass Wikipedia Denkanstöße schafft, Zusammenhänge aufzeigt und einen Überblick bieten kann. Neue Artikel, wie zum Beispiel Elektronische Bibliothek Schweiz oder Primo Central, stehen jedoch eher da wie Inseln im Informationsdschungel, um eine mißglückte Metapher zu bemühen (@LIBREAS habt ihr was zu gescheiterten Metaphern?). Auf den Inseln lässt sich es sich zwar leben, geographische Grundkenntnisse bleiben aber begrenzt.

In einer Studie zum Lernverhalten im Internetzeitalter fasste kürzlich ein Tutor das Problem für die passive Wikipedia-Nutzung zusammen:

The problem with Wikipedia is it’s too easy. You can go to Wikipedia, you can get an answer, you don’t actually learn anything, you just get an answer.

Dies gilt ähnlicher Weise auch für die aktive Wikipedia-Nutzung durch das Anlegen von Artikeln. Man lernt zwar etwas über den Gegenstand des Artikels und wie man einen Artikel schreibt. Das Verständnis der Zusammenhänge bleibt jedoch eher gering, solange nicht ein ganzes Teilnetz von thematisch verwandten Artikeln überarbeitet wird.

Can SOBR help publishing library holdings?

2. Dezember 2011 um 01:08 6 KommentareI just participated in the German conference Semantic Web in Bibliotheken which took place in Hamburg this week. This year there were two slots for lightning talks, but unfortunately participants did not catch on, so we only had four of them. Lightning talks are a good chance to present something unfinished that you need input for, so I presented the Simplified Ontology for Bibliographic Resources (SOBR) as „FRBR light“. You can find the current specification of SOBR at github, which means the specification is still evolving and I’d like to get more feedback.

SOBR was caused by a discussion on the Library Linked Data mailing list about the (disputed) disjointedness of FRBR classes. SOBR has a history in the Document Availability Information API (DAIA), which SOBR might be merged into. The use case of both is publishing information about holdings from library catalogs as Linked Open Data. The information most requested is probably connected to holdings: library users only ask „where is it?“ and „how can I get it?“. In this questions, the little word „it“ refers to a specific publication. In the answers, however, „it“ usually refers to some holding or copy of this publication. Sometimes the holding contains more than the publication (for instance if you ask for an article in a book) and sometimes you get multiple holdings (for instance if you ask for a a large work that is split in multiple volumes). Sometimes there are multiple holdings with different content to choose from, because there are different editions, forms, translations etc. of the requested publication.

A long time ago, some librarians thought about similar questions and answers and came up with the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR). I tried hard to accept FRBR (I even draw this ugly diagrams that people find when they look up FRBR in Wikipedia). But FRBR does not help me to publish existing library catalogs as Linked Open Data. In our catalog databases we have records that refer to editions, connected with records that refer to holdings (I’ll ignore the little exceptions and nasty special cases such as multiple holdings described by one look-like-a-holding-record). In addition there are some records that refer to series, works, and other types of abstract documents without direct holdings, which are connected to records that refer to editions.

Maybe we can simplify this to two entities: general documents (bibo:Document) and items (with frbr:Item) as special kind of documents. The current design of SOBR also contains a class for editions, but I am not sure whether this class is also needed. At least we need three properties to relate documents to items (daia:exemplar), to relate documents to editions (daia:edition?) and to relate documents to its parts (dcterms:hasPart). To avoid the need of blank nodes, I’d also define properties that relate documents to partial items (daia:extract = dcterms:hasPart + daia:exemplar) and to relate documents to partial editions (daia:editionPart?)

Feedback on SOBR is welcome, especially if you provide examples with existing URIs (or at least local identifiers to already existing data) instead of theoretical FRBR-like-made-up examples. The best way to find a good ontology for publishing library holdings is to actually publish data that describes library holdings! The following image is based on an example that connects a work from LibraryThing and from DBPedia with a partial edition from Worldcat, a full edition from German National Library, and a holding from Hamburg University:

@prefix bibo: <http://purl.org/ontology/bibo/> .

@prefix daia: <http://purl.org/ontology/daia/> .

@prefix frbr: <http://purl.org/vocab/frbr/core#> .

@prefix owl: <http://www.w3.org/2002/07/owl#> .

@prefix dct: <http://purl.org/dc/terms/> .

@prefix rdfs: <http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#> .

<http://www.librarything.com/work/70394> a bibo:Document ;

owl:sameAs <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Living_My_Life> ;

daia:edition <http://d-nb.info/1001703464> , [

a bibo:Collection # , daia:Document

; dct:hasPart <http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/656754414>

]

;

# daia:exemplar <http://d-nb.info/1001703464> ; ?

daia:editionPart <http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/656754414> .

<http://d-nb.info/1001703464> a frbr:Item , bibo:Document ;

daia:exemplar <http://uri.gbv.de/document/opac-de-18:epn:1220640794> .

image created with rdfdot

Die Männer im Postpatriarchat: ratlos

27. November 2011 um 02:59 16 KommentareVor einigen Tagen schrieb Antje Schrupp einen Blogartikel über Die Männer und das Patriarchat. Darin berichtet sie von einem Artikel des Philosophen Riccardo Fanciullacci über das „Ende des Patriarchats“. Eine kürzere Zusammenfassung von Schrupps Artikel gibt es bei Daniel Ehniss. Mit dem „Ende des Patriarchats“ ist nicht gemeint, dass das Patriachat, also die systematische Privilegierung von Männern, überwunden wäre. Die Bekämpfung des Patriarchats ist nur nicht mehr das Zentrum feministischer Betätigung. Diese These kann ich zumindest basierend auf der regelmäßigen Lektüre von feministischen Medien wie Missy Magazin oder Mädchenmannschaft nachvollziehen. Diese Medien würde ich mal grob einer Art von neuem Feminismus zuordnen, der einfach keinen Bock mehr darauf hat, dauernd anderen ihr Sexistisches Verhalten erklären zu müssen. Auffallend im Vergleich zum früheren (Differenz-?)Feminismus ist vielleicht noch die explizite Einbeziehung von Gender-Themen, d.h. es wird davon ausgegangen, dass „Mann“ und „Frau“ vor allem soziale Konstrukte sind, die überwunden werden müssen (hier wird dann häufig Judith Butler angeführt, was ich hiermit ungelesen auch mache und damit vermutlich „männliches Redeverhalten“ und poserhaftes Mackertum demonstriere).

Für feministische Frauen ist jedenfalls das Patriarchat zumindest theoretisch erledigt: jegliche Setzung des Männlichen als Norm ist einfach nur noch lächerlich. Männer können das Patriarchat dagegen nicht so einfach abschütteln, so Fanciullaccis These. Ich möchte hier nicht weiter auf seine Schlussfolgerungen in drei konkreten Vorschlägen eingehen, zumal ich sie zumindest für fragwürdig halte. Mit der Ausgangsthese stimme ich jedoch überein. Grundvoraussetzung ist dabei natürlich, dass das Patriarchat abgeschafft gehört, d.h. eine gewisse pro-feministische Grundhaltung. Doch was kommt nach dem Patriarchat? Diese Frage ist vor allem ein Problem für die Männern, denn sie können sich nicht einfach in Luft auflösen oder ihr Geschlecht völlig aufgeben.

Nach der Lektüre von Antje Schrupps Artikel habe ich versucht irgendwelche Online-Communities o.Ä. zu finden, in denen Themen wie die Ausgestaltung einer post-patriachalen Männlichkeit diskutiert werden. Leider stößt man dabei fast ausschließlich auf maskulistische Scheiße. Der Maskulismus ist eine sehr verbreitete Reaktion auf die Herausforderung des Postpatriarchats. Etwas vereinfacht gesagt, wünschen sich Maskulisten die „Gute alte Zeit zurück, wo Männer noch echte Männer und Frauen noch richtige Frauen waren“. Dies geht meist einher mit Homophobie und der Ablehung von Geschlechtsidentitäten jenseit von Mann und Frau. Ich kann die Sehnsucht nach einfachen, klaren Rollenbildern nachvollziehen, das ist aber natürlich der völlig falsche Weg. Ebenso falsch ist übrigens das Augen-Zu-Prinzip der Idee von „post-gender“, nach der das Patriarchat schon überwunden wäre und somit alle bitte schön zur Tagesordnung übergehen sollten.

Einige Männer, die sich mit ihrer Ratlosigkeit auseinandersetzen, habe ich dennoch gefunden. Sicher lässt sich auch noch an die Männerbewegung der 1970er und 80er anknüpfen, mir ging es aber vor allem um das hier und jetzt. Es wäre schön, wenn nach dem oben genannten neuen Feminismus auch die pro-feministische Männerbewegung ein Revival erlebt. Adrian Lang schlägt die Einrichtung von (pro-)feministischen Männergruppen vor und hat schon einige Interessenten aber auch Widerspruch gefunden. Yaneaffar fragt ob Männer Feministen sein können. Obgleich ich beiden zustimmen kann, beschränkt sich das Interesse für meinen Geschmack noch etwas zu sehr auf Anti-Sexismus: Aktionen wie das in den Kommentaren angeführte Macker Massaker sind richtig und wichtig, beantworten aber nicht die Frage nach einem neuen Männerbild. Daneben gibt es noch die Kritische Männlichkeitsforschung, die jedoch eher akademisch-theoretisch bleibt. Im Englischen gibt es das Magazin XY Online, das sich pro-Feministisch mit einer Vielzahl von Männerthemen auseinandersetzt. Sowas würde ich mir auch im deutschsprachigen Raum wünschen!

P.S.: Inzwischen habe ich die Schweizer „Männerzeitung“ gefunden. Sieht zwar etwas dröger aus als das Missy-Magazin und bezieht sich oft speziell auf die Zustände in der Schweiz, aber zumindest gegen Anti-Feminismus.

P.P.S: Es gibt sie doch noch, eine deutschsprachige, Männerbewegung, die nicht völlig merkbefreit ist: inzwischen habe ich die Vereine Dissens e.V. und AGENS e.V. (letzterer nur bedingt empfehlenswert) sowie die Zeitschrift Switchboard gefunden und einiges zur akademischen Männerforschung zusammengetragen. Und Arne Hoffmann legt dar, wie im Netz leider eine rechtslastige Minderheit der Männerbewegung den Ton angibt.

Alt-Tab in Ubuntu 11.10 ist kaputt

26. November 2011 um 13:01 1 KommentarMit Ubuntu 11.10 setzt Canonical nun ganz auf die Benutzeroberfläche Unity. Das nertv viele Ubuntu-Anwender, die nun auf andere Distributionen ausweichen. Ich persönlich finde es in Ordnung, sich ab und zu an andere Oberflächen zu gewöhnen. Das einzige was wirklich sehr stört, ist dass die seit Jahrzehnten auf verschiedenen Betriebssystemen gewohnte Umschaltung mit Alt-Tab zwischen Fenstern von Canonical kaputtgemacht wurde. Im Ubuntu-Forum bei Stackexchange gibt es einen Thread dazu, wie das bisherige Verhalten wieder hergestellt werden kann. Leider wird dazu das Konfigurationsprogram ccsw benötigt, mit dem man sich leicht aus Versehen die gesamte Benutzeroberfläche kaputtkonfigurieren kann. Vor dem Update auf Ubuntu 11.10 muss deshalb gewarnt werden. Eine etwas einfachere Möglichkeit, das bisherige Verhalten von Alt-Tab einzustellen, hätte doch gereicht. Kein Wundern, dass sich viele Anwender nach Alternativen umsehen, denn wer weiß was noch für Bevormundungen mit den nächsten Ubuntu-Versionen kommen?

URI namespace lookup with prefix.cc and RDF::NS

3. November 2011 um 17:13 Keine KommentareProbably the best feature of RDF is that it forces you to use Uniform Resource Identifiers (URI) instead of private, local identifiers which only make sense in a some context. URIs are long and cumbersome to type, so popular URIs are abbreviated with namespaces prefixes. For instance foaf:Person is expanded to http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/Person, once you have defined prefix foaf for namespace http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/. In theory URI prefixes in RDF are arbitrary (in contrast to XML where prefixes can matter, in contrast to popular belief). In practice people prefer to agree to one or two known prefixes for common URI namespaces (unless they want to obfuscate human readers of RDF data).

So URI prefixes and namespaces and are vital for handling RDF. However, you still have to define them in almost every file and application. In the end people have copy & paste the same prefix definitions again and again. Fortunately Richard Cyganiak created a registry of popular URI namespaces, called prefix.cc (it’s open source), so people at least know where to copy & paste from. I had enough of copying the same URI prefixes from prefix.cc over and over again, so I created a Perl module that includes snapshots of the prefix.cc database. It includes a simple command line client, that is installed automatically:

$ sudo cpanm RDF::NS $ rdfns rdf,foaf.ttl @prefix foaf: <http: //xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/> . @prefix rdf: <http: //www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#> .

In your Perl code, you can use it like this:

use RDF::NS

my $NS = RDF::NS->new('20111102');

$NS->foaf_Person; # returns "http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/Person"

If you miss an URI prefix, just add it at http://prefix.cc, and will be included in the next release.

Die Grenzen des Semantic Web

2. November 2011 um 18:42 4 KommentareEs gibt mehrere Gründe dafür, warum das Semantic Web, so wie es vor etwa zehn Jahren vorgeschlagen wurde, nicht funktioniert. Die wesentlichen Kritiken sind bereits vor mehreren Jahren vorgebracht worden und haben seitdem nichts von ihrer Gültigkeit verloren. Inzwischen ist deshalb eher von „Linked Data“ statt von „semantisch“ die Rede, ohne jedoch auf die Werbewirkung von „semantischen Technologien“ zu verzichten.

Aufgrund der hohen Erwartungen, die so am Leben erhalten werden, gibt es immer wieder Erstaunen, wenn die Versprechen eingelöst werden sollen. Letzt Woche wurde beispielsweise von einer Praxis-Studie berichtet, bei der einige einfache Fragen mit verknüpften RDF-Daten beantwortet werden sollten (Reck, Ronald P., Kenneth B. Sall and Wendy A. Swanbeck: Determining the Impact of Eric Clapton on Music Using RDF Graphs: Selected Challenges of Semantics Across and Within Datasets. Balisage 2011). Die Studie erinnerte mich an den vergeblichen Versuch im letzten Jahr, eine einfache Frage mit Linked Data zu beantworten. Schuld sind anscheinend die uneinheitlichen und inkonsistenten Daten. Genaugenommen sind es aber die Menschen und die Realität, welche sich einfach nicht an starre Schemas und Regeln halten wollen, sondern in unzählige Einzelfälle zerfallen. Deshalb ist der Versuch, menschliches Beurteilungsvermögen automatisieren zu können, eine Illusion.

Die Grenzen des Semantic Web liegen dort, wo Menschen verschiedene Quellen beurteilen und aus unterschiedlichen Informationen Schlussfolgerungen ziehen. Diese Schlussfolgerungen haben aber wenig mit automatischen Schlussfolgerung und Inferenz-Regeln zu tun, sondern mit dem gesunden Menschenverstand und persönlichen Entscheidungen. Kein noch so ausgeklügeltes System kann uns die Aufgabe abnehmen, selber den Verstand zu benutzen.

Wie die Studien zeigen, führt der Versuch, denken zu automatisieren, im Semantic Web zu sinnlosen und falschen Ergebnissen. Dies passiert umso schneller, je mehr Daten aus verschiedenen Quellen zusammengeführt, und ohne Nachzudenken (d.h. automatisch) mit Schlussfolgerungsregeln zu weiteren Daten verarbeitet werden („Six degrees of fallacy“). Deshalb ist es sinnvoller, Quellen einzeln und gezielt auszuwählen. Dies gilt vor allem für die Auswahl von Ontologien und automatischen Ableitungsregeln. Dass dabei Ontologie je nach Anwendungsfall umgedeutet und verändert werden, ist unumgänglich. Andernfalls müsste für jede Anwendung eine komplett eigene Ontologie erstellt werden.

Trotz aller Kritik halte ich Semantic Web und Linked Data jedoch nicht für Mythen vom Paradies auf Erden: Solange man sich darüber bewusst ist, dass sich Menschen nicht grundsätzlich ändern lassen, ist es nicht nur legitim sondern unverzichtbar,

daran zu arbeitem dem Paradies näher zu kommen. Das heisst nicht, dass wir irgendwann im Semantischen Datenhimmel ankommen; zumindest lassen sich aber einige Probleme der Aggregation von Metadaten mit RDF etwas abmildern – nicht mehr und nicht weniger.

TPDL 2011 Doctoral Consortium – part 3

25. September 2011 um 17:36 Keine KommentareSee also part 1 and part 2 of conference-blogging and #TPDL2011 on twitter.

My talk about general patterns in data was recieved well and I got some helpful input. I will write about it later. Steffen Hennicke, another PhD student of my supervisor Stefan Gradman, then talked about his work on modeling Archival Finding Aids, which are possibly expressed in EAD. The structure of EAD is often not suitable to answer user needs. For this reason Hennicke analyses EAD data and reference questions, to develope better structures that users can follow to find what they look for in archives. This is done in CIDOC-CRM as a high-level ontology and the main result will be an expanded EAD model in RDF. To me the problem of „semantic gaps“ is interesting, and I think about using some of Hennicke data as example to explain data patterns in my work.

The last talk by Rita Strebe was about aesthetical user experience of websites. One aim of her work is to measure the significance of aesthetical perception. In particular her hypothesis to be evaluated by experiments are:

H1: On a high level, the viscerally perceived visual aesthetics of websites effects

approach behaviour.

H2: On a low level, the viscerally perceived visual aesthetics of websites effects

avoidance behaviour.

Methods and preliminary results look valid, but the relation to digital libraries seems low and so was the expertise of Strebe’s motivation and methods among the participants. I suppose her work better fits to Human-Computer Interaction.

After the official part of the program Vladimir Viro briefly presented his music search engine peachnote.com, that is based on scanned muscial scores. If I was working in or with musical libraries, I would not hesitate to contact Viro! I also though about a search for free musical scores in Wikimedia framework. The Doctoral Consortium ended with a general discussion about dissertation, science, libraries, users, and everything, as it should be 🙂

Neueste Kommentare