SWIB + MTSR = SSSO

4. Dezember 2012 um 15:48 3 KommentareOn my flight back from the Metadata and Semantics Research conference (MTRS) I thought how to proceed with an RDF encoding of patron information, which I had presented before at the Sematic Web in Libraries conference (SWIB). I have written about the Patrons Account Information API (PAIA) before in this blog and you watch my SWIB slides and a video recording.

As I said in the talk, PAIA is primarily designed as API but it includes a conceptual model, which can be mapped to RDF. The term „conceptual model“ needs some clarification: when dealing with some way to express information in data, one should have a conceptual model in her or his head. This model can be made explicit, but most times people prefer to directly use formal languages, such as OWL, or they even neglect the need of conceptual modeling languages at all. People that deal with conceptual modeling languages, on the other hand, often underestimate the importance of implementations – to them RDF is just a technology that is subject to change while models are independent from technology. Examples from the cultural domain include the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (CIDOC-CRM) and the Cultural Heritage Abstract Reference Model (CHARM), which I got to know in a talk at MTSR.

So thinking about conceptual models, RDF and patron information I came up with an expression of loan status in a library. In PAIA expressed as API we have defined six (actually five) status:

- 0: no relation

- 1. reserved (the document is not accesible for the patron yet, but it will be)

- 2. ordered (the document is beeing made accesible for the patron)

- 3. held (the document is on loan by the patron)

- 4. provided (the document is ready to be used by the patron)

- 5. rejected (the document is not accesible at all)

This list defines a data type, which one can happily work with without need to think about RDF, models, and all this stuff. But there is a model behind the list, which could also be expressed in different forms in RDF.

The first decision was to express each status as an event that connects patron, library, and document during a specific time. The second decision was to not put this into a PAIA ontology but into a little, specialized ontology that could also be used for other services. It turned out that lending a book in a library is not that different to having your hair cut at a barber or ordering a product from an online shop. So I created the Simple Service Status Ontology (SSSO), which eventually defines five OWL classes:

- A ReservedService has been accepted for fulfillment but no action has taken place.

- A PreparedService is being prepared but fulfillment has not actually started.

- A ProvidedService is ready to be fulfilled immediately on request.

- An ExecutedService is actually being fulfilled.

- A RejectedService has been refused or stopped before normal termination.

Service events can be connected through time, for instance a service can be executed directly after reservation or it could first be prepared. Putting this tiny model into the Semantic Web is not trivial: I found not less than eight (sic!) existing ontologies that define an „Event“, which a SSSO Service is subclass of. Maybe there are even more. As always feedback is very welcome to finalize SSSO.

Bibliographies of data repositories

30. Juli 2012 um 13:09 2 KommentareDatabib, a proposed bibliography of research data repositories is calling for editors. These editors shall review submissions and edits to the bibliography. There is already an advisory board, giving Databib an academic touch.

The number of data repositories is growing fast, so it’s good to have an overview of existing repositories such as Databib. The number of similar collections of data repositories, however, is also growing. For instance, as noted by Daniel Kinzler in response to me, there is datahub.io hosted by the Open Knowledge Foundation and edited by volunteers. There is no advisory board, giving datahub.io an open community touch. And there are lists such as the list of repositories known to DataCite, the wiki-based list at Open Access Directory, the DFG-funded re3data.org project (which will likely be closed after funding stops, as known from most DFG funded projects), and many, many more.

One may ask why people cannot agree on either one list of repositories or at least one interchange format to create a virtual bibliography. Welcome to the multifaceted world of cataloging! I think there are reasons to have multiple collections, for instance there are different groups of users and different definitions of a [research] data repository (if there is any definition at all). At least one should be clear about the following:

Any list or collection of data repositories is an instance of a bibliography similar to a library catalog. Managing bibliographies and catalogs is more difficult than some imagine but it’s nothing new and it’s no rocket science. So people should not try to reinvent the wheel but build on established cataloging practices. Above all, one should (re)use identifiers to refer to repositories and one should not just ask for free-text input but use existing controlled vocabularies and authority files. This should also be familiar to people used to Linked Open Data.

By the way, any collection of data repositories, again is a data repository. Adding another level above may not really help. Maybe one should just treat published research data as one instance of a digital publication and catalog it together with other publications? What defines a „dataset“ in contrast to other digital publications? In the end it’s all a stream of bits isn’t it? 😉

Why do Wikimedia projects fail to deliver open content?

10. Juni 2012 um 01:02 3 KommentareFrom time to time I’d like to link to a famous quotation. I then remember Wikiquote, a wiki-based „quote compendium“ similar to Wikipedia, also run by the Wikimedia Foundation. Or I’d like to link to a famous text, and I visit Wikisource, an „online library of free content publications“, also Wikimedia project since years. But even when the quotation or text is included in Wikiquote/Wikisource, I most times leave depressed. This also applies to other Wikimedia projects, such as Wiktionary, Wikibooks, Wikimedia Commons, and even Wikipedia to some degree.

failed open content or just perpetual beta?

The reason has been mentioned by Gerard Meijssen at the Wikimedia Berlin Hackathon (#wmdevdays) a few days ago. He wrote that „Both #Wikibooks and #Wikisource do a terrible job promoting their finished product.“ I’d like to stress that Wikimedia projects do not (only) fail promoting, but they fail delivering their products. That’s sad, because Wikimedia projects are about collecting and creating open content, which anyone should be able to reuse. But conrtent is not truly open when it is only available for reuse by experts. For instance, why can’t one just…

- …link to a single quotation in Wikiquote? (WTF?!)

- …highlight a section in Wikipedia and get a stable link to this selection?

- …download content from Wikibooks, Wikisource, or Wikipedia in different formats such as EPUB, LaTeX, MarkDown, OpenDocument etc.?

- …find out the precise license of a media file from Commons?

Most of these tasks are possible if you are an expert in Wikimedia projects. You have to learn a crude WikiSyntax, know about MediaWiki API and dozens of license tags, know about extensions, do error-prone conversion on your own, deal with full dumps etc. Maybe I am too harsh because I love Wikimedia. But if you are honest about its projects, you should know: they are not designed for easy reuse of content, but more about work-in-progress collaborative editing (and even editing capability is poor compared with Google Docs and Etherpad).

Gerard suggested to create another Wikimedia project for publishing but I doubt this is the right direction. There is already a feature called Quality Revisions for marking a „final“ state of a page in MediaWiki. The core problem of reusing content from Wikimedia projects is more how to actually get content in a usable form (deep link, eBook formats, LaTeX… etc.).

First draft of Patrons Account Information API (PAIA)

29. Mai 2012 um 12:09 3 KommentareIntegrated Library Systems often lack open APIs or existing services are difficult to reuse because of access restrictions, complexity, and poor documentations. This also applies to patron information, such as loans, reservations, and fees. After reviewing standards such as NCIP, SLNP, and the DLF-ILS recommendations, the Patrons Account Information API (PAIA) was specifed at the Common Library Network (GBV).

PAIA consists of a small set of precisely defined access methods to look up patron information including fees, to renew and request documents, and to cancel requests. With PAIA it should be possible to make use of all patron methods that can be access in OPAC interfaces, also in third party applications, such as mobile Apps and discovery interfaces. The specification is divided into core methods (PAIA core) and methods for authentification (PAIA auth). This design will facilitate migration from insecure username/password authentification to more flexible systems based on OAuth 2.0. OAuth is also used by major service providers such as Google, Twitter, and Facebook.

The current draft of PAIA is available at http://gbv.github.com/paia/ and comments are very welcome. The specification is hosted in a git repository, accompanied by a wiki. Both can be accessed publicly to correct and improve the specification until its final release.

PAIA complements the Document Availability Information API (DAIA) which was created to access current availability information about documents in libraries and related institutions. Both PAIA and DAIA are being designed with a mapping to RDF, to also publish library information as linked data.

Goethe erklärt das Semantic Web

20. Mai 2012 um 15:49 4 KommentareSeit Google vor einigen Tagen den „Knowledge Graph“ vorgestellt hat, rumort es in der Semantic Web Community. Klaut Google doch einfach Ideen und Techniken die seit Jahren unter der Bezeichnung „Linked Data“ und „Semantic Web“ entwickelt wurden, und verkauft das ganze unter anderem Namen neu! Ich finde sowohl die Aufregung als auch die gedankenlose Verwendung von Worten wie „Knowledge“ und „Semantic“ auf beiden Seiten albern.

Hirngespinste von denkenden Maschinen, die „Fakten“ präsentieren, als seien es objektive Urteile ohne soziale Herkunft und Kontext, sind nun eben Mainstream geworden. Dabei sind und bleiben es auch mit künstlicher Intelligenz immer Menschen, die darüber bestimmen, was Computer verknüpfen und präsentieren. Wie Frank Rieger in der FAZ gerade schrieb:

Es sind „unsere Maschinen“, nicht „die Maschinen“. Sie haben […] kein Bewusstsein, keinen Willen, keine Absichten. Sie werden konstruiert, gebaut und eingesetzt von Menschen, die damit Absichten und Ziele verfolgen – dem Zeitgeist folgend, meist die Maximierung von Profit und Machtpositionen.

In abgeschwächter Form tritt der Irrglaube von wissenden Computern in der Fokussierung auf „Information“ auf, während in den meisten Fällen stattdessen Daten verarbeitet werden. Statt eines „Knowledge Graph“ hätte ich deshalb lieber einen „Document Graph“, in dem sich Herkunft und Veränderungen von Aussagen zurückverfolgen lassen. Ted Nelson, der Erfinder des Hypertext hat dafür die Bezeichnung „Docuverse“ geschaffen. Wie er in seiner Korrektur von Tim Berners-Lee schreibt: „not ‘all the world’s information’, but all the world’s documents.“ Diese Transparenz liegt jedoch nicht im Interesse von Google; der Semantic-Web-Community ist sie die Behandlung von Aussagen über Aussagen schlicht zu aufwendig.

Laut lachen musste ich deshalb, als Google ein weiteres Blogposting zur Publikation von gewichteten Wortlisten mit einem Zitat aus Goethes Faust beginnen lässt:

Yet in each word some concept there must be…

Im „Docuverse“ wäre dieses Zitat durch Transklusion so eingebettet, dass sich sich der Weg zum Original zurückverfolgen ließe. Hier der Kontext des Zitat von Wikisource:

Mephistopheles: […] Im Ganzen – haltet euch an Worte! Dann geht ihr durch die sichre Pforte Zum Tempel der Gewißheit ein.

Schüler: Doch ein Begriff muß bey dem Worte seyn.

Mephistopheles: Schon gut! Nur muß man sich nicht allzu ängstlich quälen; Denn eben wo Begriffe fehlen, Da stellt ein Wort zur rechten Zeit sich ein. Mit Worten läßt sich trefflich streiten, Mit Worten ein System bereiten, An Worte läßt sich trefflich glauben, Von einem Wort läßt sich kein Jota rauben.

Die Antwort von Google (und nicht nur Google) auf den zitierten Einwand des Schülers gleicht nämlich bei näherer Betrachtung der Antwort des Teufels, wobei das „System“ das uns hier „bereitet“ wird ein algorithmisches ist, das nicht auf Begriffen sondern auf Wortlisten und anderen statistischen Verfahren beruht.

In der Zeitschrift für kritische Theorie führt Marcus Hawel zu eben diesem Zitat Goethes (bzw. Googles) aus, dass Begriffe unkritisch bleiben, solange sie nur positivistisch, ohne Berücksichtigung des „Seinsollen des Dings“, das bestehende „verdoppeln“ (vgl. Adorno). Wenn Google, dem Semantic Web oder irgend einem anderen Computersystem jedoch normative Macht zugebilligt wird, hört der Spaß auf (und das nicht nur aufgrund der Paradoxien deontischer Logik). Mir scheint, es mangelt in der semantischen Knowledge-Welt an Sprachkritik, Semiotik und kritischer Theorie.

HTTP Content negotiation and format selection

9. März 2012 um 15:33 2 KommentareIn University of Southampton’s WebTeam Blog Christopher Gutteridge just complained that HTTP content negotiation could do better. And he is right. In a nutshell, content negotiation allows to retrieve different forms, versions or representations of a digital document at the same URI.

Content negotiation is an important part of the Web architecture, but sucks for several reasons. The main problem is: there is no consensus about what defines a format/version/representation etc. and how to refer to selected forms of a digital document. At least for selection by different versions in time, there is a good specification with Memento and Accept-Datetime header. Content negotiation by language (Accept-Language) is similar unless you want to query by other aspects of language (slang, readability…), because language tags are clearly defined and precise. But the concept of „content types“ (Accept header, also known as MIME types) is rather fuzzy.

Earlier I wrote about the difficulties to define „publication types“ – it’s the same problem: there is no disjoint set of content types, document types, publication types, or formats! Each document and each representation can belong to multiple types and types may overlap. The easiest case, described by Christopher, is a subset relation between two types: for instance every XML document is also a Unicode string (be warned: there is no hierarchy of types, but maybe a Directed Acyclic Graph!). Not even this simple relationship between content types can be handled by HTTP content negotiation.

Anyway, the real reason for writing this post is yet another CPAN module I wrote: Plack::App::unAPI implements unAPI. unAPI is a kind of „poor man’s content negotiation“. Instead of sending additional HTTP headers, you directly select a format with format=... parameters. In contrast to HTTP Content negotiation, an unAPI server also returns a list of all formats it supports. This is a strong argument for unAPI in my opinion. I also added a method to combine unAPI with HTTP content negotiation.

BibSonomy usability disaster

8. März 2012 um 12:01 1 KommentarIn addition to other citation management systems, I use BibSonomy. It’s one of the less known social cataloging tools. Not as commercial and shiny as Mendeley, but useful, especially if you happen to collect many papers in computer sciences. The BibSonomy team is open and friendly and the project is connected to the local University in Kassel (by the way, they are hiring students!). I still like BibSonomy – that’s why I wrote this rant.

Since last week BibSonomy has a new layout. Sure people always complain when you change their used interface, but this change is a usability desaster – at least if you work on a netbook with small screen, like me. To illustrate the problems here is a screenshot with my quick notes in red:

The screen is crowded with irritating and ugly user interface elements. The actual usage area is put into a little frame. Yes, a frame, in 2012! You cannot just scroll down to get rid of the header, because the frame is fixed. There are more flaws, for instance the duplication of account elements, scattered at not less than four places (logged in as…, logout, user:…, myBibsobomy) and the ugly custom icons (there are several great icon sets that could be used instead, for instance Silk, GCons, Glyphicons, Picol…). It does not get better of you try to edit content. I am sorry, but this is a usability disaster.

P.S: The BibSonomy team has responded and they fixed part of the problem with a nasty hack, based on actual screen size.

Embedded diagrams and pandoc

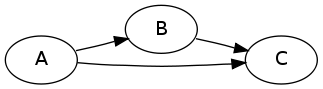

24. Januar 2012 um 13:02 Keine KommentareIf you don’t know John MacFarlane’s Pandoc, the „Swiss army knive of document formats“, you should definitely give it a try! Pandoc’s abstract document model and its serialization in an extended variant of Markdown markup let you focus on the structure and content of a text instead of dealing with formats and user interfaces. In my opinion pandoc is the best tool for document creation invented since (La)TeX (moreover pandoc is a good argument to finally learn programming in Haskell) Images in pandoc markdown documents, however, are only referenced by their file. This requires some preprocessing if you want to create different files for different document formats, especially bitmap images and vector images. So I hacked a little preprocessing script that let’s you embed images in pandoc’s markup language. For instance you write

~~~~ {.dot .Grankdir:LR}

digraph {

A -> B -> C;

A -> C;

}

~~~~

and you get

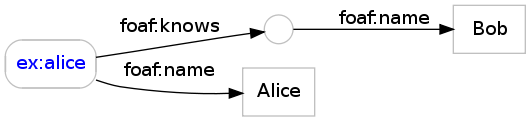

or based on rdfdot you write

~~~~ {.rdfdot}

@prefix foaf: <http: //xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/> .

@base <http: //example.com/> .

<alice> foaf:name „Alice“ ;

foaf:knows [ foaf:name „Bob“ ] .

~~~~

and you get

A detailed description is included in the manual which has been transformed automatically to HTML and to PDF. Compare both documents to see that HTML includes PNG images and PDF contains vector images!

Feel free to reuse and modify the script, for instance by adding more diagram types! For instance how about ASCII tabs and ABC notation if you write about music?

Linked local library data simplified

10. Januar 2012 um 14:53 1 KommentarA few days ago Lukas Koster wrote an article about local library linked data. He argues that bibliographic data from libraries data as linked data is not „the most interesting type of data that libraries can provide“. Instead „library data that is really unique and interesting is administrative information about holdings and circulation“. So libraries „should focus on holdings and circulation data, and for the rest link to available bibliographic metadata as much as possible.“ I fully agree with this statements but not with the exact method how do accomplish the publication of local library data.

Among other project, Koster points to LibraryCloud to aggregate and deliver library metadata, but it looks like they reinvent yet more wheels in form of their own APIS and formats for search and for bibliographic description. Maybe I am wrong about this project, as they just started to collect holding and circulation data.

At the recent Semantic Web in Bibliotheken conference, Magnus Pfeffer gave a presentation about „Publishing and consuming library loan information as linked open data“ (see slides) and I talked about a Simplified Ontology for Bibliographic Resources (SOBR) which is mainly based on the DAIA data model. We are going to align both data models and I hope that the next libraries will first look at these existing solutions instead of inventing yet another data format or ontology. Koster’s proposal, however, looks like such another solution: he argues that „we need an extra explicit level to link physical Items owned by the library or online subscriptions of the library to the appropriate shared network level“ and suggests to introduce a „holding“ level. So there would be five levels of description:

- Work

- Expression

- Manifestation

- Holding

- Item

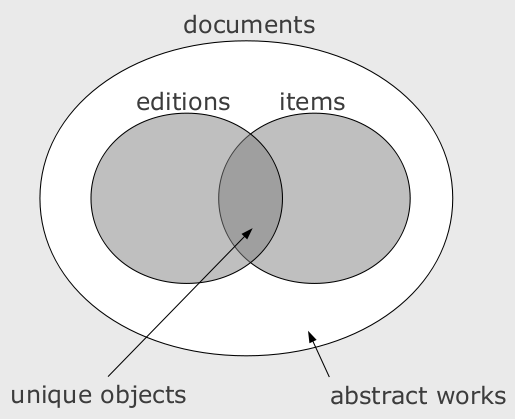

Apart from the fact that at least one of Work, Expression, Manifestation is dispensable, I disagree with a Holding level above the Item. My current model consists of at most three levels of documents:

- document as abstract work (frbr:Work, schema:CreativeWork…)

- bibliographic document (frbr:Manifestation, sobr:Edition…)

- item as concrete single copy (frbr:Item…)

The term „level“ is misleading because these classes are not disjoint. I depicted their relationship in a simple Venn diagram:

For local library data, we are interested in single items, which are copies of general documents or editions. Where do Koster’s „holding“ entities fit into this model? He writes „a specific Holding in this way would indicate that a specific library has one or more copies (Items) of a specific edition of a work (Manifestation), or offers access to an online digital article by way of a subscription.“ The core concepts as I read them are:

- „one or more copies (Items)“ = frbr:Item

- „specific edition of a work (Manifestation)“ = sobr:Edition or frbr:Manifestation

- „has one […] or offer access to“ = ???

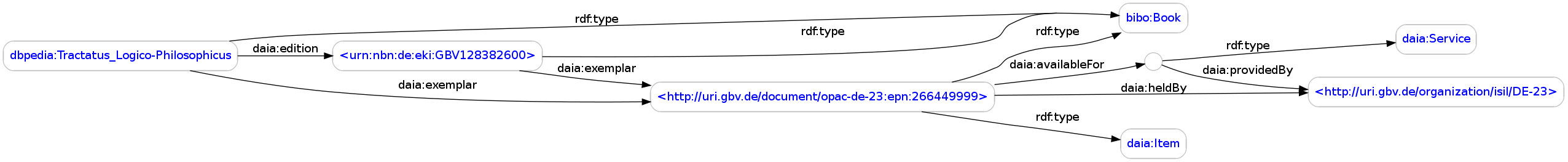

Instead of creating another entity for holdings, you can express the ability „to have one or offer access to“ by DAIA Services. The class daia:Service can be used for an unspecified service and more specific subclasses such as loan, presentation, and openaccess can be used if more is known. Here is a real example with all „levels“:

<http://dbpedia.org/resource/Tractatus_Logico-Philosophicus>

a bibo:Book ;

daia:edition <urn:nbn:de:eki:GBV128382600> ;

daia:exemplar

<http://uri.gbv.de/document/opac-de-23:epn:266449999> .

<urn:nbn:de:eki:GBV128382600> a bibo:Book ;

daia:exemplar

<http://uri.gbv.de/document/opac-de-23:epn:266449999> .

<http://uri.gbv.de/document/opac-de-23:epn:266449999>

a bibo:Book, daia:Item ;

daia:heldBy <http://uri.gbv.de/organization/isil/DE-23> ;

daia:availableFor [

a daia:Service ;

daia:providedBy <http://uri.gbv.de/organization/isil/DE-23>

] .

I have only made up the RDF property daia:edition from the SOBR proposal because FRBR relations are too strict. If you know a better relation to directly relate an abstract work to a concrete edition, please let me know.

image created with rdfdot

Request for comments: final specification of DAIA

6. Januar 2012 um 12:13 4 KommentareWhen I started to create an API for availability lookup of document in libraries in 2008, I was suprised that such a basic service was so poorly defined. The best I could find was the just-published recommendation of the Digital Library Federation (DLF-ILS). Even there availability status was basically a plain text message (section 6.3.1 and appendix 4 and 5). Other parts of the DLF-ILS GetAvailability response were more helpful, so they are all part of the Document Availability Information API (DAIA). Here is a simple mapping from DLF-ILS to DAIA:

- bibliographicIdentifer (string) → document (URI)

- itemIdentifier (string) → item (URI)

- dateAvailable (dateTime) → expected (xs:dateTime or xs:date or „unknown“) or delay (xs:duration or „unknown“)

- location (string) → storage (URI and/or string, plus optional URL)

- call number (string) → label (string)

- holdQueueLength (int) → queue (xs:nonNegativeInteger)

- status (string) and circulating (boolean) → available/unavailable (with service type and additional information)

So you could say that DAIA implements the abstract GetAvailability function from DLF-ILS. I like abstract, language independent specifications, but they must be precise and testable (see Meek’s forgotten paper The seven golden rules for producing language-independent standards). DAIA is more than an implementation: it provides both, an abstract standard and bindings to several data languages (XML, JSON, and RDF). The conceptual DAIA data model defines some basic concepts and relationships (document, items, organisations, locations, services, availabilities, limitations…) independent from whether they are expressed in XML elements, attributes, RDF properties, classes, or any other data structuring method. The only reference to specific formats is the requirement that all unique identifiers must be URIs. Right now there is an XML Schema if you want to express DAIA in XML and an OWL ontology for RDF.

In its fourth year of development (see my previous posts from 2009) DAIA seems to have enough momentum to finally get accepted in practice. We use it in GBV library union (public server at http://daia.gbv.de/), there are independent implementations such as in Doctor-Doc, there is client-support in VuFind and I heard rumors that DAIA capabilities will be build into EBSCO and Summon Discovery Services. Native support in Integrated Library Systems, however, is still lacking – I already have given up hope and prefer a clean DAIA wrapper over a broken DAIA-implementation anyway. If you are interested in creating your own DAIA server/wrapper or client, have a look at my reference implementation DAIA and Plack::App::DAIA at CPAN and Oliver Goldschmidt’s PHP implementation in our common github repository. A conceptual overview as tree (DAIA/JSON, DAIA/XML) and as graph (DAIA/RDF) can be found here.

Still there are some details to be defined and I’d like to solve these issues to come to a version DAIA 1.0. These are

- How to deal with partial publications (you requested an article but only get the full book or you requested a series but only get a single volume).

- How to deal with digital publications (especially its possible service types: is „download“ a service distinct to „loan“ or is „presentation“ similar to online access restricted to the library’s intranet?).

- Final agreement on service types (now there are presentation: item can be used in the institution, loan: item can be used outside of the institution for a limited time, interloan: item can be send to another institution, openaccess: item can be access unrestricted, just get a free copy). Some extensions have been proposed.

- A set of common limitation types (for instance IP-based access restriction, permission-based access etc.).

I’d be happy to get some more feedback on these issues, especially concrete use cases. We are already discussing on the daia-devel mailing list but you can also comment in your own blog, at public-lld, code4lib, ils-di etc.).

P.S: Following an article by Adrian I started to collect open questions and comments as issues at github

Neueste Kommentare