Professoren und Journalisten bei der Arbeit

4. Juli 2011 um 15:53 2 KommentareEigentlich hat die Geschichte um Wikipedia und Wiki-Watch.de alles was zu einem schönen Skandal dazugehört: ein universitäres Forschungsprojekt mit Verbindungen zu einer PR-Firma für Unternehmen, die sich „mit vollem Engagement für Ihre Ziele engagieren“ kann. Eine Pharmafirma mit einem Medikament, das aus gentechnisch veränderten Proteinen hergestellt wird und möglicherweise das Krebsrisiko erhöht, Verbindungen zu religiösen Extemisten, Burschenschaften und dem Videopodcast der Kanzlerin (das ich hier mal nicht verlinke), der Versuch die Aufdeckung von Plagiatsfällen zu behindern und schließlich Druck auf die Presse, falls diese wie die FAZ mal recherchiert, was die so genannten Professoren tatsächlich treiben (Kopien des Artikels siehe hier). Die Hintergründe sind mal wieder in Wikipedia nachzulesen, so dass andere Medien nicht mehr viel recherchieren müssten, um eine schöne Story daraus zu machen. Wer mag, kann das ganze mit Hintergründen zu den schädlichen Einflüssen von Drittmitteln an Hochschulen oder zur Funktion von Social Media anreichern.

Trotzdem tut sich bislang wenig in den Medien und auch die Hochschule schweigt sich lieber aus. Stattdessen müssen mal wieder Blog- und Twitter-Autoren die Aufgabe der Vierten Gewalt übernehmen, z.B. hier und hier. Aber vielleicht kommt ja noch was.

P.S.: Ich betone hiermit, dass ich mir die Inhalte der verlinkten Seiten nicht zu Eigen mache. Was im Detail davon den Tatsachen entspricht sollte jeder selber nachrecherchieren.

P.P.S.: Inzwischen gibt es einen Artikel im Spiegel und Michael Schmalenstroer hat die weiteren Entwicklungen zusammengefasst. So hat u.A. Wolfgang Stock, der zusammen mit Johannes Weberling Wiki-Watch.de betreibt, laut Spiegel eine eidesstattliche Erklärung abgegeben, die von @LobbyistenWatch widerlegt wurde. Mal sehen, ob die Lobbyisten damit durchkommen.

Was promoviere ich eigentlich?

23. Juni 2011 um 11:19 Keine KommentareSpätestens seit der Plagiatsaffäre Guttenberg und ihrer Nachfolger ist auch außerhalb von Universitäten bekannt, dass eine Promotion nicht unbedingt etwas mit wissenschaftlicher Leistung zu tun haben muss und dass es mit der akademischen Selbstkontrolle oft nicht weit her ist. Vielen Promovenden geht es vor allem darum, einen Titel zu erhalten. Das ist bis zu einem gewissen Grad auch legitim und wird durch verschiedene Faktoren gefördert; ein Grundinteresse für die eigene Dissertation sollte jedoch vorhanden sein. Im Extremfall geht der Promovend eine Beziehung zu seinem Thema ein, die Außenstehenden nur schwer verständlich zu machen ist. Einen kleinen Einblick gibt PHD Comic, dessen Top 200-Liste zum Prokrastinieren einläd.

Ich bin trotz heftigen Prokrastinierens mit meiner Dissertation inzwischen zumindest soweit, dass ich einen Einblick geben kann, über was ich eigentlich so promoviere. In der Doktoranden-Session der Konferenz Theory and Practice of Digital Libraries (TPDL) werde ich am 25. September über „concealed structures in data“ sprechen. Eine 8-Seitige Zusammenfassung habe ich bei arXiv.org veröffentlicht (in den Proceedings erscheint eine gekürzte Version von 4-Seiten). Meine Literaturliste ist bei BibSonomy einsehbar. Über Feedback jeder Art würde ich mich sehr freuen!

Europeana-Daten teilweise als Linked Data

21. Juni 2011 um 13:09 1 KommentarWie auf public-lld angekündigt, bietet Europeana seit gestern einige Daten, die von verschiedenen europäischen Kultureinrichtungen aggregiert werden, als Linked Open Data an. Der Testzugang mit Beschreibung ist unter data.europeana.eu, während im Europeana-Blog noch nichts dazu steht. Und so kommt man an die Daten: Es gibt sowohl zeinen großen Datenbankdump (etwa 1GB gepackt, 185 Millione Tripel) als auch kleinere Teile zum Herunterladen. Um die URIs einzelner Datensätze herauszubekommen, ist noch etwas Handarbeit notwendig:

- Suche im Europeana-Portal

- Einschränken des Suchergebnis auf „Free Access“

- Auswahl eines Datensatz

- Entfernen der HTTP-Query-Parameter und der Dateiendung

.htmlvon der URL, z.B.http://europeana.eu/portal/record/09428/DB8CA8BB4FABF5AE7F1B93FD6672D30A6B94B343 - Ersetze

http://europeana.eu/portal/record/durchhttp://data.europeana.eu/item/, also zum Beispielhttp://data.europeana.eu/item/09428/DB8CA8BB4FABF5AE7F1B93FD6672D30A6B94B343

Dummerweise ist damit noch nicht sicher gestellt, dass über diese URI auch RDF-Daten abgerufen werden können, da bislang nur einige Institutionen am Europeana-LOD-Pilot teilnehmen. Auch bei anderen Beispielen aus meiner Suche bekomme ich eher eine Fehlermeldung. Die in der Dokumentation angegebenen Beispiele funktionieren aber. Also gibt es erstmal keine Verknüpfung zum Normdatensatz von Livia Drusilla. Beim Ausprobieren ist mir aufgefallen, dass die Europeana-Server etwas lahm sind und dass es mir unmöglich war, sinnvoll etwas zu finden, da die meisten Objekte als „Image“ gekennzeichnet sind, statt als „Gemälde“, „Statue“, „Münze“ etc. Für praktische Linked-Data-Anwendungen wäre es hilfreich, die Suche auf Objekte einzuschränken zu können, deren Daten als Linked Data verfügbar sind.

Alles in Allem ist der Pilot ein guter Schritt in die richtige Richtung, aber noch etwas wackelig. Da es sich explizit um einen Beta-Test handelt, sollte man jedoch nicht allzu kritisch sein, sondern erstmal mit den Daten herumspielen oder abwarten was noch kommt.

Query parts in Linked Data URIs considered harmful

29. Mai 2011 um 01:40 Keine KommentareThe generic syntax of URI (and of IRI with slightly different definition of the elements) is:

<scheme name> : <hierarchical part> [ ? <query> ] [ # <fragment> ]

RDF is based on „URI references“ which have a different syntax, but all practical RDF data should follow the generic URI syntax. This is also implied by the Linked Data Principles which encourage you to use HTTP URIs. Furthermore it is a good advice not to include fragments in your URIs if you care about coexistence of the Web and the Semantic Web. Yes, there is RDF data with fragment parts and the so called Hash URIs are even given as one design pattern, but you can avoid a lot of trouble if you use URIs without them. By the way, fragment identifiers are also used a lot in JavaScript-based web applications that spoil the whole concept of REST as described in this recent in-depth article on Hash URIs.

I would even go further and say that well-designed URIs for Linked Data should also forgo the query part. A clean URI to be used as identifier in Linked Data should stick to this limited generic syntax:

http: <hierarchical part>

I do not argue to disallow URIs with query part, but I wonder how much they are really used and needed for resources other than Web resources. Especially URIs for non-information resources, should not have a query part. Most web applications will not distinguish between these two:

http://example.org?foo=1&bar=2 http://example.org?bar=2&foo=1

These are different URIs but equivalent URLs. Choosing URIs that are not equivalent to other URIs in common non-RDF applications is a good advice, isn’t it? If you choose a cleaner URI like http://example.org/foobar you could use additional query parts to refer to different representations (information resources) and services around the resource that is referenced by the base URI.

Hardware-Emulatoren im Browser

18. Mai 2011 um 00:48 1 KommentarFür die meisten Nerds war die Nachricht der letzten Tage wahrscheinlich, das Meister Fabrice Bellard einen x86-Emulator in Javascript geschrieben hat. Seine Demo bootet einen Linux-Kernel, inklusive C-Compiler, so dass er sich prinzipiell zum Bootstrapping von anderen Anwendungen verwendet werden kann. Vielleicht lässt sich auch mit MS-DOS und Turbo-C++ die Umgebung zum Laufen bekommen, mit ich mir Mitte der 1990er Programmieren beigebracht habe.

Der x86-Emulator ist jedoch nicht der einzige Emulator mit dem nicht einmal 20 Jahre alte Hardware in einem Browser-Tab simuliert werden kann. Hier einige Fundstücke:

- JSNES (Nintendo Entertaiment System)

- JSGB (GameBoy) – außerdem gibt es ein schönes Tutorial zur Entwicklung eines anderen GameBoy-Emulators

- GameBoy-Online (GameBoy Color)

- jsc64 (C64)

- JSSpeccy (Sinclair ZX Spectrum)

- Apple2JS (Apple II)

- CPCBox (Amstrad CPC)

Weitere verwandte Projekte sind unter Anderem JS/UIX (Unix in JavaScript), Emscripten (Crosscompiler zu JavaScript) und Emulatoren die als Java-Plugin im Browser laufen wie z.B. Virtual Apple ][. JavaScript hat jedoch den Vorteil, das nichts zusätzlich installiert werden muss und dass der Emulator in einer Sandbox läuft (wobei es sicher für jeden Browser JavaScript-Exploits gibt). Wirklich cool wäre ein Emulator für den NeXT auf dem Tim Berners-Lee den ersten Webbrowser entwickelte. Ich warte jetzt auf den ersten Emulator der in JavaScript eine virtuelle Maschine erzeugt, in der ein JavaScript-fähiger Browser läuft *g*

Research data, git hashes, and unbreakable links

5. Mai 2011 um 23:57 1 KommentarYesterday I had a short conversation about libraries and research data. This topic seems to be trendy, for instance D-Lib magazine just had a special issue about it. I am not quite sure about the role of libraries for the management of research data. It looks like many existing projects at least aim at analyzing research data – this can get very complex because any data can be research data. Maybe librarians should better limit to what they can do best and stick to metadata. It is not the job of librarians to analyze traditional publications (there are scientists to do so, for instance in philology), so why should they start analyzing research data? It would be easier if we just treat research data as „blobs“ (plain sequences of bytes) to not get lost in the details of data formats. There will be still enough metadata to deal with (although this metadata might better be managed by the users).

One argument in our discussion was that libraries might just use the distributed revision control system git. Git is also trendy, but among software developers that must track many files of source code with revisions and dependencies. Although git is great for source code and lousy for raw binary data, we could learn something from its architecture (actually there is an extension to git to better handle large binary files). I already knew that git uses hash sums and hash trees and was curious how it actually stores data and metadata.

Management of data in git is basically based on the SHA1 hashing algorithm, but you could also use another hashing method. This answer told me how git calculates the SHA1 for a chunk of data. Note that the name of a file is not part of the calculation, as the filename is no data but metadata. You can move around and rename a file; its hash remains the same. More details of how git stores data and metadata about collections of data chunks (filenames and commits) can be found in the git community book, in the git book and in this blog article how git stores your data.

Hashes are also used in peer-to-peer networks to reference files of unknown location. With distributed hash tables you can even decentralize the lookup mechanism. Of course someone still needs to archive the data, but if the data is stored at least somewhere in the system, it cannot get lost by wrong names or broken links. Instead of pointing to locations of files, metadata about research data should contain an unbreakable link to the data in form of its hash. Libraries that want to deal with research data can then focus on metadata. Access to data could be provided via BitTorrent or any other method. The problem of archiving is another issue that should better be solved independently from description and access.

A third trendy topic is linked data and RDF. You can use clean URIs like this to refer to any chunk of data: urn:sha1:cd50d19784897085a8d0e3e413f8612b097c03f1

To make it even more trendy (you are welcome to reuse my idea in your next library research project proposal 😉 put the data objects into the cloud. No more file names, no more storage media – data is just a link in form of a hash value and a big cloud that you can look up data chunks by their hash.

P.S: A short explanation why you can really replace any piece of (research) data by its hash: There are 2160 different SHA1 hash values. According to rules of probability the expected number of hashes that can be generated before an accidental collision („birthday paradox'“) is 280. The sun will expand in around 5 billion years (less than 258 seconds from now, making life on earth impossible. That means until then we can still generate 2^44 (4 million) hashes per second and collisions are still unlikely. With cryptographic attacks the number can be smaller but it is still much larger than other sources of error.

IT statt Informationskompetenz statt Bibliothekare?

21. April 2011 um 11:24 1 KommentarIn der englischsprachigen Biblioblogosphäre wird gerade ein kontroverser Vortrag von Jeffrey Trzeciak, dem Bibliotheksdirektor der McMaster University, Penn State, diskutiert. Angeblich möchte er alle Bibliothekare abschaffen, worauf diese natürlich lautstark protestieren. Laika (Jacqueline) hat einige Aspekte des Vortrags und der Diskussion zusammengefasst (via @tillk) und versucht etwa Sachlichkeit in die Diskussion zu bringen. Wie in vielen Kontroversen geht es nämlich leider weniger um das Abwägen von Argumenten als darum, die eigene Meinung zu bestätigen. Eine ähnliche Diskussion könnte ich mir auch in der deutschsprachigen Bibliothekswelt vorstellen: die Kontroverse bestätigt leider einen typischen Konflikt (zu dem ich zugegeben nicht immer unschuldig bin): Auf der einen Seite überheblichen IT-affine, die alles besser wissen, und auf der anderen Seite Bibliothekaren mit Minderwertigkeitskomplex, die lieber nichts neues ausprobieren. Zum Glück bilden diese beiden Extreme nur einen Teil der Bibliothekswelt ab.

In der deutschsprachigen Biblioblogosphäre haben in ihren Weblogs Anne Christensen und Dörte Böhner die Kontroverse konstruktiv aufgenommen und diskutieren den Aspekt der Informationskompetenz, die Trzeciak scheinbar gleich mit entsorgen möchte. Anne hatte schon früher auf die Problematik des Begriffs Informationskompetenz hingewiesen, aber grundsätzlich halten beide Autoren nichts davon, Veranstaltungen zur Informationskompetenz völlig abzuschaffen. Allerdings kommt es eben auf die Umsetzung an. Wie Dörte treffend schreibt:

Ein einmal eingeworfenes “Man könnte auch mit einem anderen Begriff suchen oder das und das machen…” bewirkt häufig mehr als zwei Stunden IK-Schulung, selbst nach neusten Methoden.

Was für das Verhältnis zwischen Bibliothekaren und Nutzern bezüglich Informationskompetenz gilt, gilt ebenso für das Verhältnis zwischen IT-affinen und IT-zurückhaltenden Bibliothekaren (wobei „IT“ nicht ganz der treffende Begriff ist, es geht auch um eine allgemeine Kultur des Ausprobierens). Die eine Seite ist nicht dumm oder faul, sondern beide Seiten haben habe es sich jeweils in ihrer Haltung bequem gemacht. Vielleicht hilft dagegen etwas, einfach mehr miteinander zu reden?

Mapping bibliographic record subfields to JSON

13. April 2011 um 16:26 4 KommentareThe current issue of Code4Lib journal contains an article about mapping a bibliographic record format to JSON by Luciano Ramalho. Luciano describes two approaches to express the CDS/ISIS format in a JSON structure to be used in CoudDB. The article already provoked some comments – that’s how an online journal should work!

The commentators mentioned Ross Singer’s proposal to serialize MARC in JSON and Bill Dueber’s MARC-HASH. There is also a MARC-JSON draft from Andrew Houghton, OCLC. The ISIS format reminded me at PICA format which is also based on fields and subfields. As noted by Luciano, you must preserves subfield ordering and allow for repeated subfields. The existing proposals use the following methods for subfields:

Luciano’s ISIS/JSON:

[ ["x","foo"],["a","bar"],["x","doz"] ]

Ross’s MARC/JSON:

"subfields": [ {"x":"foo"},{"a":"bar"},{"x":"doz"} ]

Bill’s MARC-HASH:

[ ["x","foo"],["a","bar"],["x","doz"] ]

Andrew’s MARC/JSON:

"subfield": [

{"code":"x","data":"foo"},{"code":"a","data":"bar"},

{"code":"x","data":"doz"} ]

In the end the specific encoding does not matter that much. Selecting the best form depends on what kind of actions and access are typical for your use case. However, I could not hesitate to throw my encoding used in luapica into the ring:

{ "foo", "bar", "doz",

["codes"] = {

["x"] = {1,3}

["a"] = {2}

}}

I think about further simplifying this to:

{ "foo", "bar", "doz", ["x"] = {1,3}, ["a"] = {2} }

If f is a field than you can access subfield values by position (f[1], f[2], f[3]) or by subfield code f[f.x[1]],f[f.a[1]],f[f.x[2]]. By overloading the table access method, and with additional functions, you can directly write f.x for f[f.x[1]] to get the first subfield value with code x and f:all("x") to get a list of all subfield values with that code. The same structure in JSON would be one of:

{ "values":["foo", "bar", "doz"], "x":[1,3], "a":[2] }

{ "values":["foo", "bar", "doz"], "codes":{"x":[1,3], "a":[2]} }

I think a good, compact mapping to JSON that includes an index could be:

[ ["x", "a", "x"], {"x":[1,3], "a":[2] },

["foo", "bar", "doz"], {"foo":[1], "bar":[2], "doz":[3] } ]

And, of course, the most compact form is:

["x","foo","a","bar","x","doz"]

Proposed changes in VIAF RDF

13. April 2011 um 13:42 2 KommentareThe Virtual International Authority File (VIAF) is one of the distinguished showcases of international library community projects. Since more then five years, name authority files from different countries are mapped in VIAF. With VIAF you can look up records about authors and other people, and see which identifiers are used for the same person in different national library catalogs. For some people there are also links to bibliographic articles in Wikipedia (I think only English Wikipedia, but you can get some mappings to other Wikipedias via MediaWiki API), and I hope that there will be links to LibraryThing author pages, too.

However, for two reasons VIAF is not used as much as it could be: first not enough easy-to-understand documentation, examples, and simple APIs; and second difficulties to adopt technologies by potential users. Unfortunately the second reason is the larger barrier: many libraries cannot even provide a simple way to directly link to publications from and/or about a specific person, once you got the right person identifier from VIAF. If you cannot even provide such a fundamental method to link to your database, how should you be able to integrate VIAF for better retrieval? VIAF can do little about this lack of technical skills in libraries, it can only help integrating VIAF services in library software to some degree. This brings me to the other reason: you can always further improve documentation, examples, the design of you APIs, etc. to simplify use of your services. As a developer I found VIAF well documented and not very difficult to use, but there are many small things that could be made better. This is natural and a good thing, if you communicate with your users and adopt suggested changes, as VIAF does.

For instance yesterday Jeffrey A. Young, one of the developers behind VIAF at OCLC published a blog article about proposed changes to the RDF encoding of VIAF. I hope that other people will join the discussion so we can make VIAF more usable. There is also a discussion about the changes at the library linked data mailing list. And earlier this month, at the Code4Lib mailing list, there was a a controversial thread about the problems to map authority records that are not about people (see my statement here).

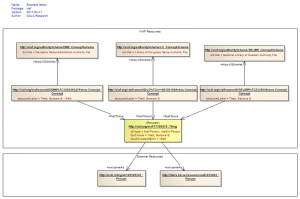

I appreciate the simplification of VIAF RDF and only disagree in some details. The current proposal is illustrated in this picture (copied from Jeffrey’s original article):

This looks straightforward, doesn’t it? But it only suits for simple one-to-one mappings. Any attempt to put more complex mappings into this scheme (as well as the existing VIAF RDF scheme) will result in a disaster. There is nothing wrong with simple one-to-one mappings, with SKOS you can even express different kinds of mappings (broader, narrower, exact, close), but you should not expect too much preciseness and detail. I wonder why at one side of the diagram links are expressed via foaf:focus and at the other side via owl:sameAs. In my opinion, as VIAF is about mapping authority files, all mapping links should use SKOS mapping properties. There is nothing wrong in declaring an URI like http://viaf.org/viaf/39377930/ to stand for both a foaf:Person, a rdaEnt:Person, and a skos:Concept. And the Webpage that gives you information about the person can also get the same URI (see this article for a good defense of the HTTP-303 mess). Sure Semantic Web purists, which still dream of hard artificial intelligence, will disagree. But in the end RDF data is alway about something instead of the thing itself. For practical use it would help much more to think about how to map complex concepts at the level of concept schemes (authority records, classifications, thesauri etc.) instead of trying to find a „right“ model reality. As soon as we use language (and data is a specific kind of language), all we have is concepts. In terms of RDF: using owl:Thing instead of skos:Concept in most cases is an illusion of control.

Was ist ein Publikationstyp?

7. April 2011 um 20:29 7 KommentareIm Rahmen der Weiterentwicklung von DAIA kam wiederholt der Wunsch auf, Exemplare als Netzpublikation zu kennzeichnen, so dass klar ist, dass man direkt über einen Link auf den Titel kommt. Uwe Reh wies in der Diskussion darauf hin, dass nach dem neuen Katalogisierungsstandard RDA eine „Manifestation“ (das entspricht etwa einer bestimmten Auflage oder Version einer Publikation) eine eindeutige Materialart haben muss (hier eine RDA-Übersicht zur Manifestation [PDF]). Aber ist die Materialart das Gleiche wie ein Publikationstyp?

Das Konzept des Publikationstyps hat mich schon öfter etwas genervt wenn ich von irgend einer Anwendung oder einem Datenformat gezwungen wurde, für eine Publikation einen „Typ“ auszuwählen. In BibTeX gibt es beispielsweise 14 verschiedene Typen von „article“ über „proceedings“ bis „misc“. Daneben gibt es zahlreiche andere Listen von Typen. Also was ist das eigentlich, ein Publikationstyp?

In Wikipedia gibt es dazu bislang keinen Artikel, nur verschiedene Artikel zu einzelnen Literaturgattungen, Formen von wissenschaftlichen Arbeiten, oder allgemein Formen von Publikationen. Über DBPedia ließen sich diese Listen auch zur Angabe von Publikationstypen verwenden. Das Glossar Informationskompetenz definiert Publikationstyp als „Form einer schriftlichen Veröffentlichung, von Zweck, Umfang und Inhalt bestimmt. In Katalogen und Datenbanken ist der Publikationstyp meist ein mögliches Suchkriterium, mit dem die Treffermenge bei einer Literatursuche formal eingeschränkt werden kann.“ Der Eintrag im Lexikon der Bibliotheks und Informationswissenschaft (LBI) erscheint gerade erst mit Band 9. Konrad Umlauf definiert Publikationstyp dort als “ Klasse von Publikationen mit mindestens einem gleichen Merkmal“ und weist angesichts überschneidender Begriffe wie „Dokumenttyp“, „Materialart“, „Editionsform“ und „Medientyp“ darauf hin, dass es „keinen einheitlichen Begriff von Publikationstyp“ gibt.

Wenn es jedoch keine einheitliche Definition von Publikationstyp gibt, ist der Zwang, dass eine Publikation genau einen Typ haben muss, um so unsinniger. Warum kann eine Publikation zum Beispiel nicht gleichzeitig Buch, Onlinepublikation und Dissertation sein? Oder gleichzeitig Mikroform, Onlinepublikation und Klaviernoten (die Links gehen auf die Klassifikationen von Publikationen aus RDA)? Sicher schließen sich einige der Typen aus, aber eben nicht alle. Sinnvoller wäre da eine Facettenklassifikation von Publikationstypen. Darauf werden sich die verschiedenen Anwender jedoch wahrscheinlich nie einigen werden. Stattdessen gibt es zahlreiche unabhängige Klassifikationen:

- Dublin Core Resource Types

- RDA extent

- BibTeX-Typen

- DINI-Publikationstypen für das XMetaDiss-Format

- RSWK-Formcodes nach DIN 31631

- Die Klassen der Bibliographic Ontology oder der Fabio-Ontology

- Die Publication Type Ontology für info-eu-repo

- Die vorgegebenen Typen in Literaturverwaltungsprogrammen (Citavi, Zotero, Mendeley etc.)

Vielleicht sollten wir einfach aufhören von Publikationstypen zu reden und uns stattdessen auf charakteristische Eigenschaften (Höhe, Breite, Umfang, Zielpublikum etc.) beschränken?

Neueste Kommentare