Can SOBR help publishing library holdings?

2. Dezember 2011 um 01:08 6 KommentareI just participated in the German conference Semantic Web in Bibliotheken which took place in Hamburg this week. This year there were two slots for lightning talks, but unfortunately participants did not catch on, so we only had four of them. Lightning talks are a good chance to present something unfinished that you need input for, so I presented the Simplified Ontology for Bibliographic Resources (SOBR) as „FRBR light“. You can find the current specification of SOBR at github, which means the specification is still evolving and I’d like to get more feedback.

SOBR was caused by a discussion on the Library Linked Data mailing list about the (disputed) disjointedness of FRBR classes. SOBR has a history in the Document Availability Information API (DAIA), which SOBR might be merged into. The use case of both is publishing information about holdings from library catalogs as Linked Open Data. The information most requested is probably connected to holdings: library users only ask „where is it?“ and „how can I get it?“. In this questions, the little word „it“ refers to a specific publication. In the answers, however, „it“ usually refers to some holding or copy of this publication. Sometimes the holding contains more than the publication (for instance if you ask for an article in a book) and sometimes you get multiple holdings (for instance if you ask for a a large work that is split in multiple volumes). Sometimes there are multiple holdings with different content to choose from, because there are different editions, forms, translations etc. of the requested publication.

A long time ago, some librarians thought about similar questions and answers and came up with the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR). I tried hard to accept FRBR (I even draw this ugly diagrams that people find when they look up FRBR in Wikipedia). But FRBR does not help me to publish existing library catalogs as Linked Open Data. In our catalog databases we have records that refer to editions, connected with records that refer to holdings (I’ll ignore the little exceptions and nasty special cases such as multiple holdings described by one look-like-a-holding-record). In addition there are some records that refer to series, works, and other types of abstract documents without direct holdings, which are connected to records that refer to editions.

Maybe we can simplify this to two entities: general documents (bibo:Document) and items (with frbr:Item) as special kind of documents. The current design of SOBR also contains a class for editions, but I am not sure whether this class is also needed. At least we need three properties to relate documents to items (daia:exemplar), to relate documents to editions (daia:edition?) and to relate documents to its parts (dcterms:hasPart). To avoid the need of blank nodes, I’d also define properties that relate documents to partial items (daia:extract = dcterms:hasPart + daia:exemplar) and to relate documents to partial editions (daia:editionPart?)

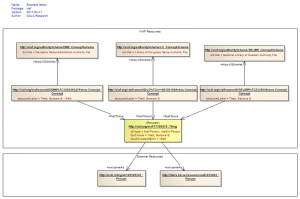

Feedback on SOBR is welcome, especially if you provide examples with existing URIs (or at least local identifiers to already existing data) instead of theoretical FRBR-like-made-up examples. The best way to find a good ontology for publishing library holdings is to actually publish data that describes library holdings! The following image is based on an example that connects a work from LibraryThing and from DBPedia with a partial edition from Worldcat, a full edition from German National Library, and a holding from Hamburg University:

@prefix bibo: <http://purl.org/ontology/bibo/> .

@prefix daia: <http://purl.org/ontology/daia/> .

@prefix frbr: <http://purl.org/vocab/frbr/core#> .

@prefix owl: <http://www.w3.org/2002/07/owl#> .

@prefix dct: <http://purl.org/dc/terms/> .

@prefix rdfs: <http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#> .

<http://www.librarything.com/work/70394> a bibo:Document ;

owl:sameAs <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Living_My_Life> ;

daia:edition <http://d-nb.info/1001703464> , [

a bibo:Collection # , daia:Document

; dct:hasPart <http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/656754414>

]

;

# daia:exemplar <http://d-nb.info/1001703464> ; ?

daia:editionPart <http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/656754414> .

<http://d-nb.info/1001703464> a frbr:Item , bibo:Document ;

daia:exemplar <http://uri.gbv.de/document/opac-de-18:epn:1220640794> .

image created with rdfdot

URI namespace lookup with prefix.cc and RDF::NS

3. November 2011 um 17:13 Keine KommentareProbably the best feature of RDF is that it forces you to use Uniform Resource Identifiers (URI) instead of private, local identifiers which only make sense in a some context. URIs are long and cumbersome to type, so popular URIs are abbreviated with namespaces prefixes. For instance foaf:Person is expanded to http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/Person, once you have defined prefix foaf for namespace http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/. In theory URI prefixes in RDF are arbitrary (in contrast to XML where prefixes can matter, in contrast to popular belief). In practice people prefer to agree to one or two known prefixes for common URI namespaces (unless they want to obfuscate human readers of RDF data).

So URI prefixes and namespaces and are vital for handling RDF. However, you still have to define them in almost every file and application. In the end people have copy & paste the same prefix definitions again and again. Fortunately Richard Cyganiak created a registry of popular URI namespaces, called prefix.cc (it’s open source), so people at least know where to copy & paste from. I had enough of copying the same URI prefixes from prefix.cc over and over again, so I created a Perl module that includes snapshots of the prefix.cc database. It includes a simple command line client, that is installed automatically:

$ sudo cpanm RDF::NS $ rdfns rdf,foaf.ttl @prefix foaf: <http: //xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/> . @prefix rdf: <http: //www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#> .

In your Perl code, you can use it like this:

use RDF::NS

my $NS = RDF::NS->new('20111102');

$NS->foaf_Person; # returns "http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/Person"

If you miss an URI prefix, just add it at http://prefix.cc, and will be included in the next release.

TPDL 2011 Doctoral Consortium – part 3

25. September 2011 um 17:36 Keine KommentareSee also part 1 and part 2 of conference-blogging and #TPDL2011 on twitter.

My talk about general patterns in data was recieved well and I got some helpful input. I will write about it later. Steffen Hennicke, another PhD student of my supervisor Stefan Gradman, then talked about his work on modeling Archival Finding Aids, which are possibly expressed in EAD. The structure of EAD is often not suitable to answer user needs. For this reason Hennicke analyses EAD data and reference questions, to develope better structures that users can follow to find what they look for in archives. This is done in CIDOC-CRM as a high-level ontology and the main result will be an expanded EAD model in RDF. To me the problem of „semantic gaps“ is interesting, and I think about using some of Hennicke data as example to explain data patterns in my work.

The last talk by Rita Strebe was about aesthetical user experience of websites. One aim of her work is to measure the significance of aesthetical perception. In particular her hypothesis to be evaluated by experiments are:

H1: On a high level, the viscerally perceived visual aesthetics of websites effects

approach behaviour.

H2: On a low level, the viscerally perceived visual aesthetics of websites effects

avoidance behaviour.

Methods and preliminary results look valid, but the relation to digital libraries seems low and so was the expertise of Strebe’s motivation and methods among the participants. I suppose her work better fits to Human-Computer Interaction.

After the official part of the program Vladimir Viro briefly presented his music search engine peachnote.com, that is based on scanned muscial scores. If I was working in or with musical libraries, I would not hesitate to contact Viro! I also though about a search for free musical scores in Wikimedia framework. The Doctoral Consortium ended with a general discussion about dissertation, science, libraries, users, and everything, as it should be 🙂

TPDL 2011 Doctoral Consortium – part 2

25. September 2011 um 12:42 Keine KommentareThe TPDL 2011 Doctoral Consortium, which I already blogged about in part 1, continued with 15 minutes of delay: Christopher Gibson also talked about eBooks – I wonder why his talk was not combined with Luca Colombo’s work in eBook reading experiences. Gibson’s specific topic is eBook lending services in UK public libraries. To quote the research questions from his paper:

Q1. How have public libraries addressed ebook service provision in the UK?

Q2. What challenges and opportunities exist in incorporating ebook lending into other reader services?

Q3. Is it feasible to lend ebook reading devices from public libraries?

Q4. How can the effectiveness of ebook lending services be measured?

Q5. How do library users view the provision of ebook lending services?

Q6. How can effective ebook lending services be developed?

To me an interesting aspect of his methodology was the use of targeted FOI (freedom of information) requests to gather data about eBook lending services. I cannot image this in this Germany where „Informationsfreiheit“ is still in its infancy. One result from another survery done by Gibson: most eBooks are not included in library catalogs. I think this failure is found in German libraries too. In summary the PhD project looked very profound with some real practical values for libraries. On the other hand, the theoretical contribution, for instance the question what „lending“ can mean in a digital library work, was only added in the discussion afterwards.

The next presenting PhD student was Adam Sofronjievic. I am sorry that I could not fully concentrate on his talk about a New Paradigm of Library Collaboration although it seemed very interesting. My talk is next 🙂

TPDL 2011 Doctoral Consortium

25. September 2011 um 11:21 2 KommentareToday the International Conference on Theory and Practice of Digital Libraries 2011 started with tutorials and a Doctoral Consortium that I participate with a talk. The seven talks and discussions on ongoing PhD topics were rather diverse and interesting. I tried to briefly summarize at least some of them.

Luco Colombo started with his work on developing and evaluating eBook reading experience for children. Reading „traditional“ books has been extensively investigated – this is not true for eBooks. Especially children are little involved in eBook studies. Colombo explained how the eBook reading experience is different because it directly involves searching, browsing, sharing, and recommending, among other arguments. A good reading experience results in a „flow state“ where the reading gets positively lost in a book. Colombo’s method is a cooperative inquiry. It is not clear whether and by what eBooks are more engaging to children (age 9-11 in this study) than traditional books – maybe this PhD will show. The following discussion was dominated by the participating mentors Jose Borbinha, Milena Dobreva, Stefan Gradmann and Giuseppina Vullo.

In the second talk Krassimira Ivanova presented her dissertation on (content-based) image retrieval utilizing color models. Image retrieval on art images is difficult because it includes very different aspects (artistic styles, depicted objects etc.). Even aspects of color (contrasts, intensity, diversity, harmony etc.) are manifold – maybe this is why philosophy of color has a long history. Nevertheless Ivanova developed several machine learning methods for this color aspects that can be used for image retrieval. I am not sure whether the resulting APICAS system („Art Painting Image Colour Aesthetics and Semantics“) has been evaluated with a user study. Similar to the first talk, the focus could be improved by more narrowing down and making clear the specific contribution. Finally we had some real discussion, but little time.

Modeling is difficult

21. September 2011 um 00:33 3 KommentareYesterday Pete Johnston wrote a detailed blog article about difficulties of „the right“ modeling with SKOS, and FOAF in general, and about the proposed RDF property foaf:focus in particular. As Dan Brickley wrote in a recent mail „foaf:focus describes a link from a skos:Concept to ‚the thing itself‘. Not every SKOS concept (in a thesauri of classification scheme) will have such a direct „thing“, but many do, especially concepts for people and places.“

Several statements in this discussion made me laugh and smile. Don’t get me wrong – I honor Pete, Dan, and the whole Semantic Web community, but there is a regular lack of philosophy and information science. There is no such thing as ‚the thing itself‘ and all SKOS concepts are equal. Even the distinction between an RDF ‚resource‘ and an SKOS ‚concept‘ is artificial. The problem origins not from wrong modeling, which could be solved by the right RDF properties, but from different paradigms and cultures. There will always be different ways to describe the same ideas with RDF, because neither RDF nor any other technology will ever fully catch our ideas. These technologies are not about things but only about data. As William Kent wrote in Data Reality (1978): „The map is not the territory“ (by the way, last year Chris Rusbridge has quoted Kent in the context of linked data). As Erik Wilde and Robert J. Glushko wrote in a great article (2008):

RDF has succeeded beyond the wildest expectations as a convenient format for encoding information in an open and easily computable fashion. But it is just a format, and the difficult work of analysis and modeling information has not and will never go away.

Ok, they referred not to „RDF“ but to „XML“, so the quotation is wrong. But the statement is right for both data structuring methods. No matter if you put your data in XML, in RDF, or carve it in stone – there will never be a final model, because there’s more than one way to describe something.

Query parts in Linked Data URIs considered harmful

29. Mai 2011 um 01:40 Keine KommentareThe generic syntax of URI (and of IRI with slightly different definition of the elements) is:

<scheme name> : <hierarchical part> [ ? <query> ] [ # <fragment> ]

RDF is based on „URI references“ which have a different syntax, but all practical RDF data should follow the generic URI syntax. This is also implied by the Linked Data Principles which encourage you to use HTTP URIs. Furthermore it is a good advice not to include fragments in your URIs if you care about coexistence of the Web and the Semantic Web. Yes, there is RDF data with fragment parts and the so called Hash URIs are even given as one design pattern, but you can avoid a lot of trouble if you use URIs without them. By the way, fragment identifiers are also used a lot in JavaScript-based web applications that spoil the whole concept of REST as described in this recent in-depth article on Hash URIs.

I would even go further and say that well-designed URIs for Linked Data should also forgo the query part. A clean URI to be used as identifier in Linked Data should stick to this limited generic syntax:

http: <hierarchical part>

I do not argue to disallow URIs with query part, but I wonder how much they are really used and needed for resources other than Web resources. Especially URIs for non-information resources, should not have a query part. Most web applications will not distinguish between these two:

http://example.org?foo=1&bar=2 http://example.org?bar=2&foo=1

These are different URIs but equivalent URLs. Choosing URIs that are not equivalent to other URIs in common non-RDF applications is a good advice, isn’t it? If you choose a cleaner URI like http://example.org/foobar you could use additional query parts to refer to different representations (information resources) and services around the resource that is referenced by the base URI.

Research data, git hashes, and unbreakable links

5. Mai 2011 um 23:57 1 KommentarYesterday I had a short conversation about libraries and research data. This topic seems to be trendy, for instance D-Lib magazine just had a special issue about it. I am not quite sure about the role of libraries for the management of research data. It looks like many existing projects at least aim at analyzing research data – this can get very complex because any data can be research data. Maybe librarians should better limit to what they can do best and stick to metadata. It is not the job of librarians to analyze traditional publications (there are scientists to do so, for instance in philology), so why should they start analyzing research data? It would be easier if we just treat research data as „blobs“ (plain sequences of bytes) to not get lost in the details of data formats. There will be still enough metadata to deal with (although this metadata might better be managed by the users).

One argument in our discussion was that libraries might just use the distributed revision control system git. Git is also trendy, but among software developers that must track many files of source code with revisions and dependencies. Although git is great for source code and lousy for raw binary data, we could learn something from its architecture (actually there is an extension to git to better handle large binary files). I already knew that git uses hash sums and hash trees and was curious how it actually stores data and metadata.

Management of data in git is basically based on the SHA1 hashing algorithm, but you could also use another hashing method. This answer told me how git calculates the SHA1 for a chunk of data. Note that the name of a file is not part of the calculation, as the filename is no data but metadata. You can move around and rename a file; its hash remains the same. More details of how git stores data and metadata about collections of data chunks (filenames and commits) can be found in the git community book, in the git book and in this blog article how git stores your data.

Hashes are also used in peer-to-peer networks to reference files of unknown location. With distributed hash tables you can even decentralize the lookup mechanism. Of course someone still needs to archive the data, but if the data is stored at least somewhere in the system, it cannot get lost by wrong names or broken links. Instead of pointing to locations of files, metadata about research data should contain an unbreakable link to the data in form of its hash. Libraries that want to deal with research data can then focus on metadata. Access to data could be provided via BitTorrent or any other method. The problem of archiving is another issue that should better be solved independently from description and access.

A third trendy topic is linked data and RDF. You can use clean URIs like this to refer to any chunk of data: urn:sha1:cd50d19784897085a8d0e3e413f8612b097c03f1

To make it even more trendy (you are welcome to reuse my idea in your next library research project proposal 😉 put the data objects into the cloud. No more file names, no more storage media – data is just a link in form of a hash value and a big cloud that you can look up data chunks by their hash.

P.S: A short explanation why you can really replace any piece of (research) data by its hash: There are 2160 different SHA1 hash values. According to rules of probability the expected number of hashes that can be generated before an accidental collision („birthday paradox'“) is 280. The sun will expand in around 5 billion years (less than 258 seconds from now, making life on earth impossible. That means until then we can still generate 2^44 (4 million) hashes per second and collisions are still unlikely. With cryptographic attacks the number can be smaller but it is still much larger than other sources of error.

Mapping bibliographic record subfields to JSON

13. April 2011 um 16:26 4 KommentareThe current issue of Code4Lib journal contains an article about mapping a bibliographic record format to JSON by Luciano Ramalho. Luciano describes two approaches to express the CDS/ISIS format in a JSON structure to be used in CoudDB. The article already provoked some comments – that’s how an online journal should work!

The commentators mentioned Ross Singer’s proposal to serialize MARC in JSON and Bill Dueber’s MARC-HASH. There is also a MARC-JSON draft from Andrew Houghton, OCLC. The ISIS format reminded me at PICA format which is also based on fields and subfields. As noted by Luciano, you must preserves subfield ordering and allow for repeated subfields. The existing proposals use the following methods for subfields:

Luciano’s ISIS/JSON:

[ ["x","foo"],["a","bar"],["x","doz"] ]

Ross’s MARC/JSON:

"subfields": [ {"x":"foo"},{"a":"bar"},{"x":"doz"} ]

Bill’s MARC-HASH:

[ ["x","foo"],["a","bar"],["x","doz"] ]

Andrew’s MARC/JSON:

"subfield": [

{"code":"x","data":"foo"},{"code":"a","data":"bar"},

{"code":"x","data":"doz"} ]

In the end the specific encoding does not matter that much. Selecting the best form depends on what kind of actions and access are typical for your use case. However, I could not hesitate to throw my encoding used in luapica into the ring:

{ "foo", "bar", "doz",

["codes"] = {

["x"] = {1,3}

["a"] = {2}

}}

I think about further simplifying this to:

{ "foo", "bar", "doz", ["x"] = {1,3}, ["a"] = {2} }

If f is a field than you can access subfield values by position (f[1], f[2], f[3]) or by subfield code f[f.x[1]],f[f.a[1]],f[f.x[2]]. By overloading the table access method, and with additional functions, you can directly write f.x for f[f.x[1]] to get the first subfield value with code x and f:all("x") to get a list of all subfield values with that code. The same structure in JSON would be one of:

{ "values":["foo", "bar", "doz"], "x":[1,3], "a":[2] }

{ "values":["foo", "bar", "doz"], "codes":{"x":[1,3], "a":[2]} }

I think a good, compact mapping to JSON that includes an index could be:

[ ["x", "a", "x"], {"x":[1,3], "a":[2] },

["foo", "bar", "doz"], {"foo":[1], "bar":[2], "doz":[3] } ]

And, of course, the most compact form is:

["x","foo","a","bar","x","doz"]

Proposed changes in VIAF RDF

13. April 2011 um 13:42 2 KommentareThe Virtual International Authority File (VIAF) is one of the distinguished showcases of international library community projects. Since more then five years, name authority files from different countries are mapped in VIAF. With VIAF you can look up records about authors and other people, and see which identifiers are used for the same person in different national library catalogs. For some people there are also links to bibliographic articles in Wikipedia (I think only English Wikipedia, but you can get some mappings to other Wikipedias via MediaWiki API), and I hope that there will be links to LibraryThing author pages, too.

However, for two reasons VIAF is not used as much as it could be: first not enough easy-to-understand documentation, examples, and simple APIs; and second difficulties to adopt technologies by potential users. Unfortunately the second reason is the larger barrier: many libraries cannot even provide a simple way to directly link to publications from and/or about a specific person, once you got the right person identifier from VIAF. If you cannot even provide such a fundamental method to link to your database, how should you be able to integrate VIAF for better retrieval? VIAF can do little about this lack of technical skills in libraries, it can only help integrating VIAF services in library software to some degree. This brings me to the other reason: you can always further improve documentation, examples, the design of you APIs, etc. to simplify use of your services. As a developer I found VIAF well documented and not very difficult to use, but there are many small things that could be made better. This is natural and a good thing, if you communicate with your users and adopt suggested changes, as VIAF does.

For instance yesterday Jeffrey A. Young, one of the developers behind VIAF at OCLC published a blog article about proposed changes to the RDF encoding of VIAF. I hope that other people will join the discussion so we can make VIAF more usable. There is also a discussion about the changes at the library linked data mailing list. And earlier this month, at the Code4Lib mailing list, there was a a controversial thread about the problems to map authority records that are not about people (see my statement here).

I appreciate the simplification of VIAF RDF and only disagree in some details. The current proposal is illustrated in this picture (copied from Jeffrey’s original article):

This looks straightforward, doesn’t it? But it only suits for simple one-to-one mappings. Any attempt to put more complex mappings into this scheme (as well as the existing VIAF RDF scheme) will result in a disaster. There is nothing wrong with simple one-to-one mappings, with SKOS you can even express different kinds of mappings (broader, narrower, exact, close), but you should not expect too much preciseness and detail. I wonder why at one side of the diagram links are expressed via foaf:focus and at the other side via owl:sameAs. In my opinion, as VIAF is about mapping authority files, all mapping links should use SKOS mapping properties. There is nothing wrong in declaring an URI like http://viaf.org/viaf/39377930/ to stand for both a foaf:Person, a rdaEnt:Person, and a skos:Concept. And the Webpage that gives you information about the person can also get the same URI (see this article for a good defense of the HTTP-303 mess). Sure Semantic Web purists, which still dream of hard artificial intelligence, will disagree. But in the end RDF data is alway about something instead of the thing itself. For practical use it would help much more to think about how to map complex concepts at the level of concept schemes (authority records, classifications, thesauri etc.) instead of trying to find a „right“ model reality. As soon as we use language (and data is a specific kind of language), all we have is concepts. In terms of RDF: using owl:Thing instead of skos:Concept in most cases is an illusion of control.

Neueste Kommentare